May 3, 2017

Navigating Religion and Science in the ICU

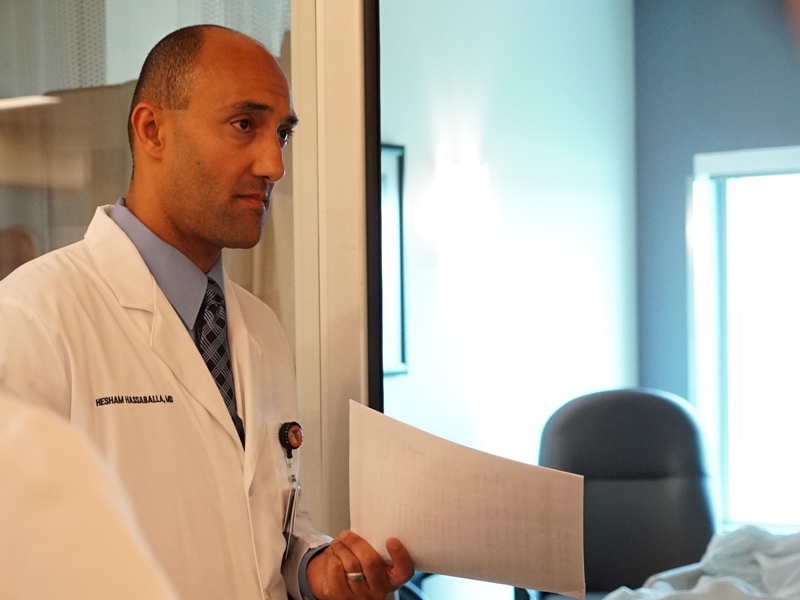

“We believe in God.” This is a frequent response by patients’ family members to my team and me in the intensive care unit after we explain to them that, despite everything we have done, the disease ravaging their loved one may likely take his life. Critical illness is difficult to understand for many people not in the healthcare field. It can take a perfectly healthy human being and render her near death in a matter of hours – or even minutes. It is difficult to understand that, just because the heart is beating, it does not mean that their beloved son or father will ever walk out of the intensive care unit alive. This is what the science says, and in many cases, the science is right. “But we believe in God,” they say, “and His will be done. Whatever He wants will happen.” This is their signal to my team and me that they don’t believe us, and they want us to continue the most aggressive treatment measures at our disposal to keep their loved one “alive.” This is despite the fact that such measures – as the science tells us – will only continue suffering and prolong the time to the patient’s inevitable demise. I try my utmost to be respectful, avoiding any sign of disapproval at their intransigence, and respond by saying, “Well, I believe in God as well.” As a man of faith, I fully understand and agree with the statement that “His will be done. Whatever He wants will happen.” I live and breathe this reality every day, not only in my daily life, but as a critical care specialist. It is one of the most glorious things about being a physician: I am witness firsthand to the amazing power of God’s creative genius in the human body. The physiologic systems in our bodies are extraordinary in their complexity, keeping each organ system within a very narrow set of normal limits. If the pH of the human blood, for instance, decreases by a mere 0.5 points – from 7.4 to 6.9 – this can kill instantly. The fact that most people are born and live healthy lives is nothing short of a miracle. And, as a critical care specialist who also has religious faith, I am witness firsthand to the amazing power of God’s healing. Of course, medical science and technology has advanced to a truly unprecedented degree. There are things we can do as physicians today that were beyond the scope of even the most imaginative minds one hundred years ago. I see this as a tremendous blessing from God, and using this blessing, I can take someone from the brink of death and watch her walk out of the hospital alive and well. Words can never do true justice to the amazing feeling this gives me. It is why I became a physician in the first place. And with each patient I treat, with each success and – yes – occasional failure, my experience and scientific expertise grows more robust. And, therefore, this allows me to speak with confidence to a frightened family in the intensive care unit that their loved one will likely not survive. This confidence, however, is humble. This confidence is humbled by numerous experiences where the science said that patient should not survive, but he or she survived anyway. The converse is also true: there have been numerous instances in my career where the science said the treatments rendered were appropriate; the science said that patient should survive this illness. Unfortunately, however, the patient did not survive. This, in fact, is exactly what happened with my daughter. My eldest daughter suffered from a rare genetic disorder, Ataxia-Telangiectasia, which leaves children unable to walk and enduring various degrees of immune system dysfunction. My daughter had an incredibly weak immune system, and she suffered from repeated infections throughout her entire life. One of the complications of A-T, as the disease is also known, is cancer, and at the age of 12, she was diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. She underwent six cycles of harsh chemotherapy, as the lymphoma was extremely aggressive and widespread at the time of her initial diagnosis. By the time we reached the last cycle, which was supposed to be the easiest, her little body could not take any more. The side effects of the chemotherapy – the terribly painful mucositis that made it very difficult to eat and the low white blood cell counts – would not go away like they did with all the previous cycles. Then, the fever and diarrhea started. For one week straight, she had unrelenting fever and diarrhea, despite being on appropriate, broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. She was in terrible pain, and she knew the pain medication “Dilaudid” by name. It was torture watching her go through so much suffering, but I had faith that she would pull through, just like she did all with all the previous cycles. Things, however, did not go as they previously did. During the early morning hours of Saturday, June 8, 2009, something changed. She was less responsive, breathing more heavily, and her heart rate was much faster that it had been heretofore. She was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. Despite everything they did, she continued to deteriorate. By the end of the night, she was placed on a ventilator and transferred to another hospital for possible dialysis. After arriving there, she developed shock that became refractory, and by the next morning, her pupils were “fixed and dilated,” which meant that her brain had suffered irreparable damage and death was imminent. By noon on Sunday, June 9, 2009, my eldest daughter was dead. Until a few hours before her death, I could not see it. I understood all the science; I understood all the medical terminology; I understood all the treatments being given to her, and I agreed that they were all appropriate. If it was any other patient, it would have been obvious, but, I could not see it. I could not see that my daughter was dying. I had faith – until the very end – that she would pull through and make it out of the hospital alive. Therefore, I understand where the families of patients come from when they tell me, “We believe in God.” I understand that it is very difficult to grasp that their loved one may very well die. I understand that they have full faith that their loved one will pull through and make it out of the hospital alive because, “God can do anything.” People speak about the “dialogue” between science and religious faith. Many times, however, I do not see a dialogue, but rather a shouting match. This can be especially true in places like the intensive care unit. Each side – the medical, “scientific” side and the “religious” side – talks past each other, leaving the patient in the middle, continuing to suffer undue pain and torment. Yet, there can be a dialogue, and a productive one to boot. For me, the dialogue between science and religion has been harmonious and healthy. The more I practice medicine in the intensive care unit, the more in awe of God I become. My religious faith has only strengthened my abilities as a physician, and it has allowed me to comfort patients and their families in times of crisis and dire need. “Yes, I believe God can do anything,” I may say to a family member holding on to faithful hope. “But, sometimes, God wills that people die. And it may very well happen to your loved one.” I then follow up with my own experience, to let them know that I truly understand their pain: “Look, I know how you feel. I lost my own daughter to cancer.” “Yet,” I continue, “I know I am not God. If, after we stop the aggressive treatments, John survives, then that is God’s will. I will not be upset. I do not mind if I am wrong. But, if he does pass away, then there is nothing to feel guilty about. You did nothing wrong.” And most of the time, this interaction ends well, and the patient is relieved of their suffering. Now, of course, there are the few times when the family refuses to accept that their loved one has already died, believing that he will “rise from the dead” once again. This too needs patience and explanation that, even though the heart is beating, the brain has died, and therefore by law, the patient has died, and we must disconnect him from life support. Once, I was told “don’t sign that death certificate just yet,” by a family member who was convinced that her prayers over the already dead loved one – his heart had long stopped beating – would bring him back to life. I let her finish her prayer, out of respect for her beliefs. While I also believe God can bring the dead back to life, I was certain it would not happen on that day (and, of course, I was right). Times of crisis are one of the instances when people rely upon religious faith, and we in healthcare need to be more comfortable in dealing with it. It is not a traditional part of our training as physicians. Yes, we had one class in medical school about cultural awareness, but once I became a resident and fellow, there was no formal training on how to deal with, for example, the Muslim patient that refuses life-saving blood thinners because they come from pigs. We need to be comfortable dealing within the world of religious faith, because it is very important to a substantial proportion of patients and their families, especially in the face of life-threatening illness. What’s more, being facile with religious faith and its terminology is very important when discussing goals of care and what one wants at the end of life. Failing to do so is a disservice to our patients and their families and loved ones. This does not mean all physicians should adopt religious faith, but it is a call for more understanding on the part of healthcare providers of the worldview of those who do have religious faith. When I know a patient or his family is religious, and they thank me for “saving his life,” I tell them, “It is God who heals. I only fill out the paperwork.” We all get a laugh from this, but it highlights that being a physician of faith allows me to have a connection with my patients on another level. This makes my job all the more satisfying, and for that, I only have God to thank.